The main reason my wife I bought our home in Algonquin, IL, was for its mature oaks. We have a collection of white, bur and red oaks in our yard. The biggest is a bur oak measuring 140 inches in diameter.

As much as the large trees are inspiring, I would like to write about the unsung heroes of the ecosystem: the snags. When I am clearing the understory overgrowth, I girdle a few unwanted trees rather than cutting them down completely. Although some would consider this unsightly, the habitat value created merits attention.

In my profession of landscape architect, I had the opportunity to work on the Orange County Great Park (OCGP) project in Irvine, CA a decade ago. The aim was to convert a retired Marine Corps air base into a park with a recreated canyon system where a tarmac once covered the ground. This exceptional project was the biggest and most ambitious in the country at the time.

It was the beginning stages of the process, when emphasis was on research and development of elements to include. At the time, I was familiar with the ecological role of snags but had never undertaken a concerted effort into studying them. During this process, I came across an article from England on creating snags in public parks. The process was not to simply girdle an existing tree, but to anchor a trunk in place to mimic a snag habitat.

As my research grew into creating specific habitats, it became clear the very important role of snags and downed logs in establishing healthy ecosystems. Dead wood and downed logs play a significant role in providing habitat for many creatures.

To me, it seems that conservation efforts in the Midwest rarely include snags. They are recognized for their value but are not introduced along with planting plans. I suspect part of the reason is the risk of introducing dead wood that might harbor pests.

I carried this interest to my own yard. To create a snag, need to select areas that do not pose a danger to people and infrastructure, such as your home or overhead wires. It takes a while from the time a tree is girdled to when it becomes a suitable habitat. For example, I estimate that it takes a good three years for woodpeckers to start using it. The snags will eventually tumble and need replacement if you wish to continue to provide such habitats. If this is your aim, it is wise not to cut all the unwanted trees at once, but to stagger them so that snags are available for a good length of time.

Even on the ground, snags will be home to many other creatures as well as lichens, mosses, and mushrooms. Salamanders, for example, depend on old decaying logs to lay their eggs.

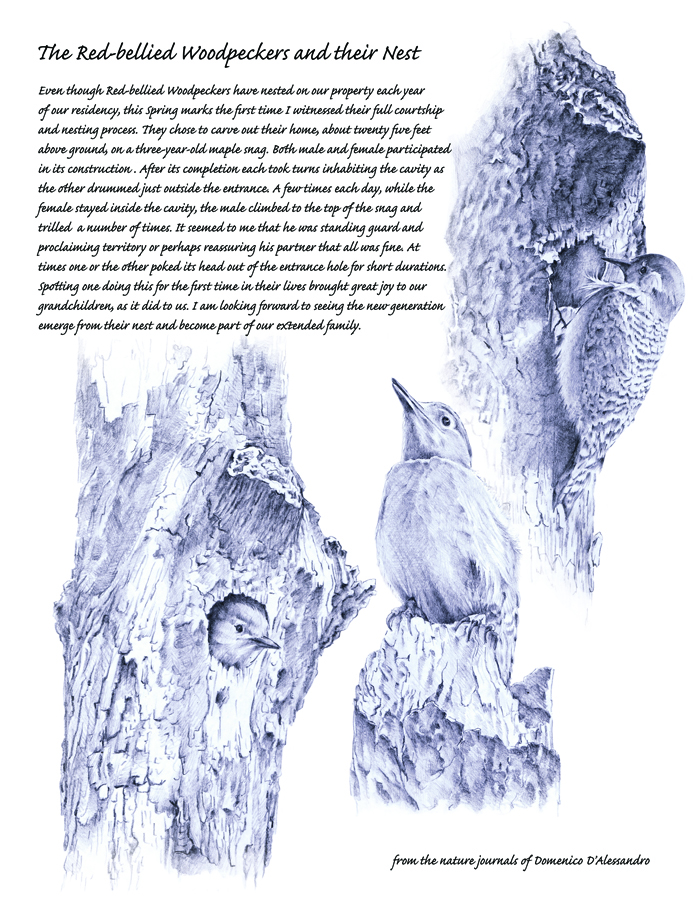

Too often, we neglect nature’s cycles and interfere by tidying things up to suit our aesthetic preferences. I wrote about a particular snag and the red-bellied woodpeckers that made it their home in one of my nature journal pages, published in Illinois Audubon magazine.

As we rightly appreciate the majestic spread of a living tree, let us not neglect the importance it has once down and not be so hasty to clear it away.